Page 34 - Remedial Andrology

P. 34

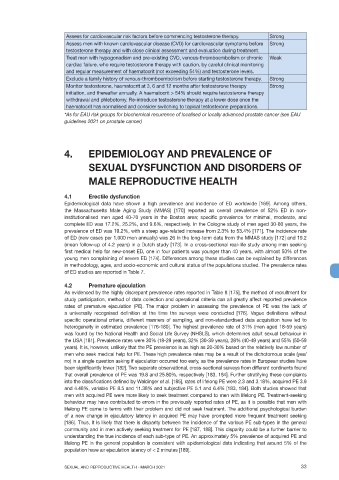

Assess for cardiovascular risk factors before commencing testosterone therapy. Strong

Assess men with known cardiovascular disease (CVD) for cardiovascular symptoms before Strong

testosterone therapy and with close clinical assessment and evaluation during treatment.

Treat men with hypogonadism and pre-existing CVD, venous-thromboembolism or chronic Weak

cardiac failure, who require testosterone therapy with caution, by careful clinical monitoring

and regular measurement of haematocrit (not exceeding 54%) and testosterone levels.

Exclude a family history of venous-thromboembolism before starting testosterone therapy. Strong

Monitor testosterone, haematocrit at 3, 6 and 12 months after testosterone therapy Strong

initiation, and thereafter annually. A haematocrit > 54% should require testosterone therapy

withdrawal and phlebotomy. Re-introduce testosterone therapy at a lower dose once the

haematocrit has normalised and consider switching to topical testosterone preparations.

*As for EAU risk groups for biochemical recurrence of localised or locally advanced prostate cancer (see EAU

guidelines 2021 on prostate cancer)

4. EPIDEMIOLOGY AND PREVALENCE OF

SEXUAL DYSFUNCTION AND DISORDERS OF

MALE REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH

4.1 Erectile dysfunction

Epidemiological data have shown a high prevalence and incidence of ED worldwide [169]. Among others,

the Massachusetts Male Aging Study (MMAS) [170] reported an overall prevalence of 52% ED in non-

institutionalised men aged 40-70 years in the Boston area; specific prevalence for minimal, moderate, and

complete ED was 17.2%, 25.2%, and 9.6%, respectively. In the Cologne study of men aged 30-80 years, the

prevalence of ED was 19.2%, with a steep age-related increase from 2.3% to 53.4% [171]. The incidence rate

of ED (new cases per 1,000 men annually) was 26 in the long-term data from the MMAS study [172] and 19.2

(mean follow-up of 4.2 years) in a Dutch study [173]. In a cross-sectional real-life study among men seeking

first medical help for new-onset ED, one in four patients was younger than 40 years, with almost 50% of the

young men complaining of severe ED [174]. Differences among these studies can be explained by differences

in methodology, ages, and socio-economic and cultural status of the populations studied. The prevalence rates

of ED studies are reported in Table 7.

4.2 Premature ejaculation

As evidenced by the highly discrepant prevalence rates reported in Table 8 [175], the method of recruitment for

study participation, method of data collection and operational criteria can all greatly affect reported prevalence

rates of premature ejaculation (PE). The major problem in assessing the prevalence of PE was the lack of

a universally recognised definition at the time the surveys were conducted [176]. Vague definitions without

specific operational criteria, different manners of sampling, and non-standardised data acquisition have led to

heterogeneity in estimated prevalence [176-180]. The highest prevalence rate of 31% (men aged 18-59 years)

was found by the National Health and Social Life Survey (NHSLS), which determines adult sexual behaviour in

the USA [181]. Prevalence rates were 30% (18-29 years), 32% (30-39 years), 28% (40-49 years) and 55% (50-59

years). It is, however, unlikely that the PE prevalence is as high as 20-30% based on the relatively low number of

men who seek medical help for PE. These high prevalence rates may be a result of the dichotomous scale (yes/

no) in a single question asking if ejaculation occurred too early, as the prevalence rates in European studies have

been significantly lower [182]. Two separate observational, cross-sectional surveys from different continents found

that overall prevalence of PE was 19.8 and 25.80%, respectively [183, 184]. Further stratifying these complaints

into the classifications defined by Waldinger et al. [185], rates of lifelong PE were 2.3 and 3.18%, acquired PE 3.9

and 4.48%, variable PE 8.5 and 11.38% and subjective PE 5.1 and 6.4% [183, 184]. Both studies showed that

men with acquired PE were more likely to seek treatment compared to men with lifelong PE. Treatment-seeking

behaviour may have contributed to errors in the previously reported rates of PE, as it is possible that men with

lifelong PE came to terms with their problem and did not seek treatment. The additional psychological burden

of a new change in ejaculatory latency in acquired PE may have prompted more frequent treatment seeking

[186]. Thus, it is likely that there is disparity between the incidence of the various PE sub-types in the general

community and in men actively seeking treatment for PE [187, 188]. This disparity could be a further barrier to

understanding the true incidence of each sub-type of PE. An approximately 5% prevalence of acquired PE and

lifelong PE in the general population is consistent with epidemiological data indicating that around 5% of the

population have an ejaculation latency of < 2 minutes [189].

SEXUAL AND REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH - MARCH 2021 33